Page 1

Loading page image...

Page 2

Loading page image...

Page 3

Loading page image...

Page 4

Loading page image...

Page 5

Loading page image...

Page 6

Loading page image...

Page 7

Loading page image...

Page 8

Loading page image...

Page 9

Loading page image...

Page 10

Loading page image...

Page 11

Loading page image...

Page 12

Loading page image...

Page 13

Loading page image...

Page 14

Loading page image...

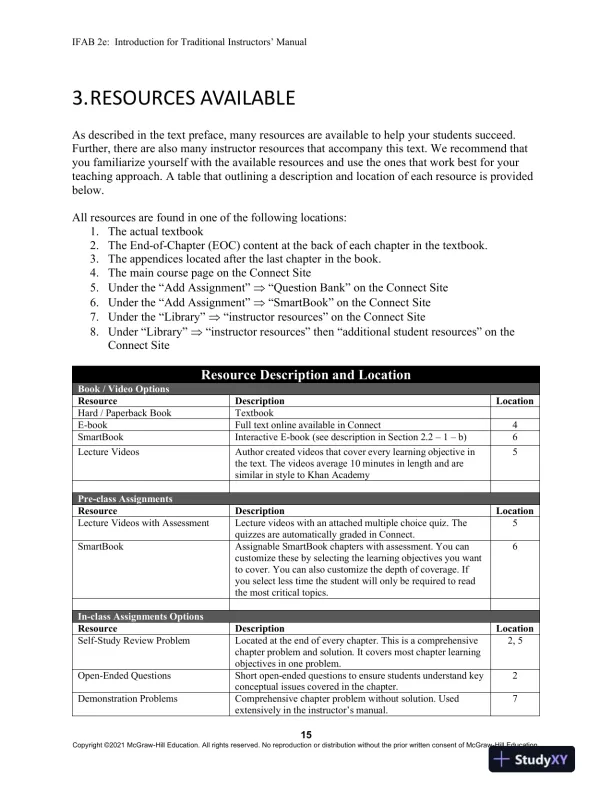

Page 15

Loading page image...

Page 16

Loading page image...