Page 1

Loading page image...

Page 2

Loading page image...

Page 3

Loading page image...

Page 4

Loading page image...

Page 5

Loading page image...

Page 6

Loading page image...

Page 7

Loading page image...

Page 8

Loading page image...

Page 9

Loading page image...

Page 10

Loading page image...

Page 11

Loading page image...

Page 12

Loading page image...

Page 13

Loading page image...

Page 14

Loading page image...

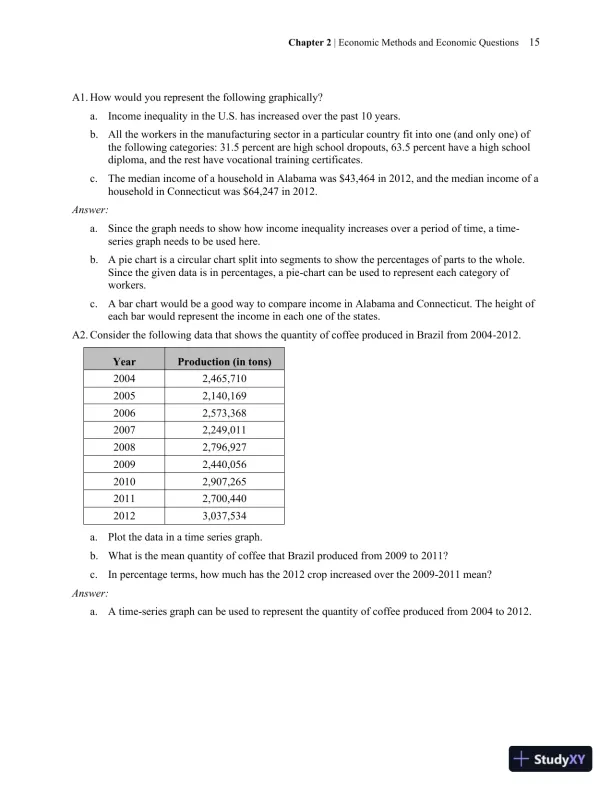

Page 15

Loading page image...

Page 16

Loading page image...

Page 17

Loading page image...

Page 18

Loading page image...

Page 19

Loading page image...

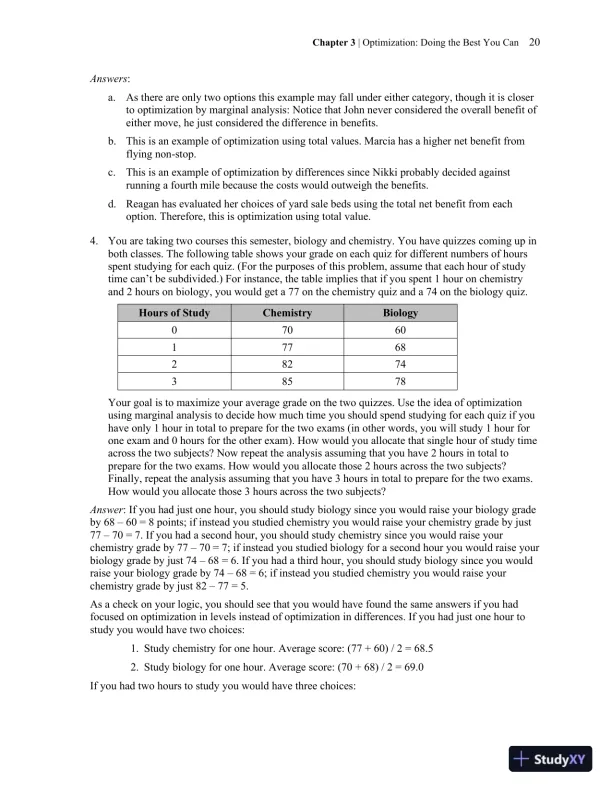

Page 20

Loading page image...

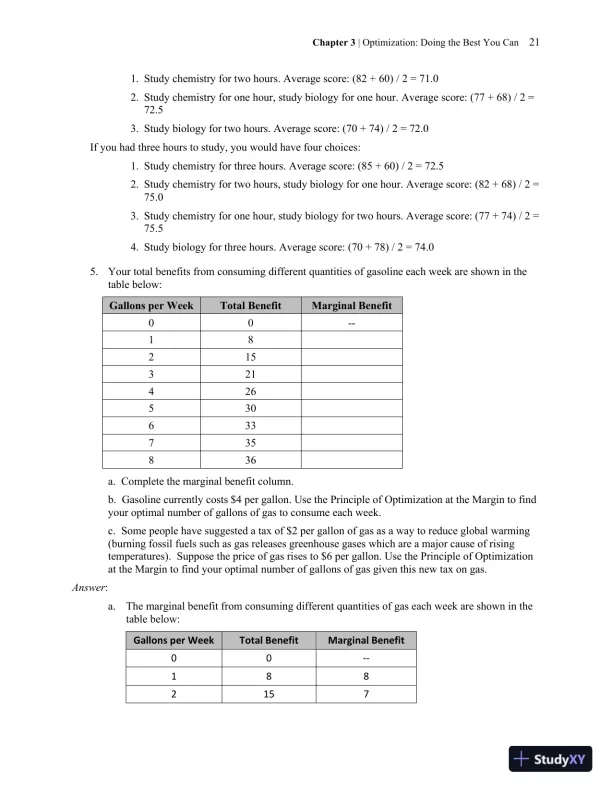

Page 21

Loading page image...

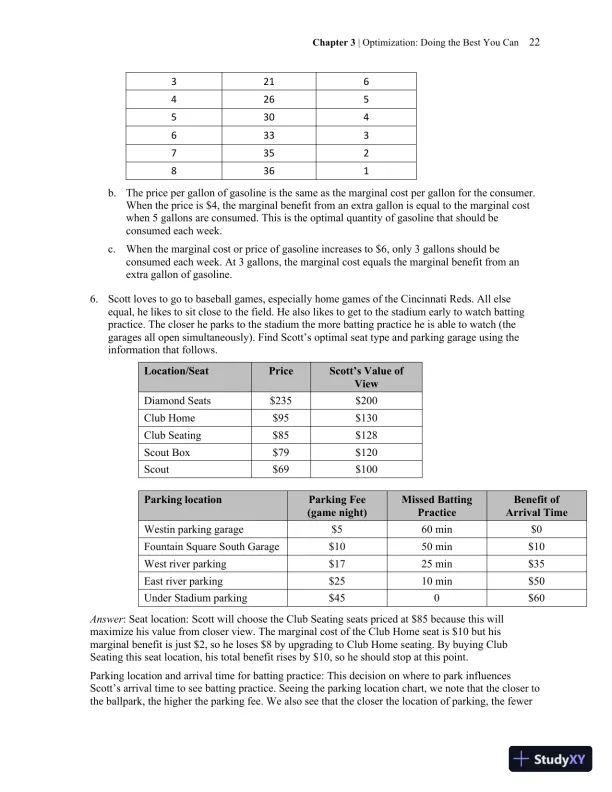

Page 22

Loading page image...

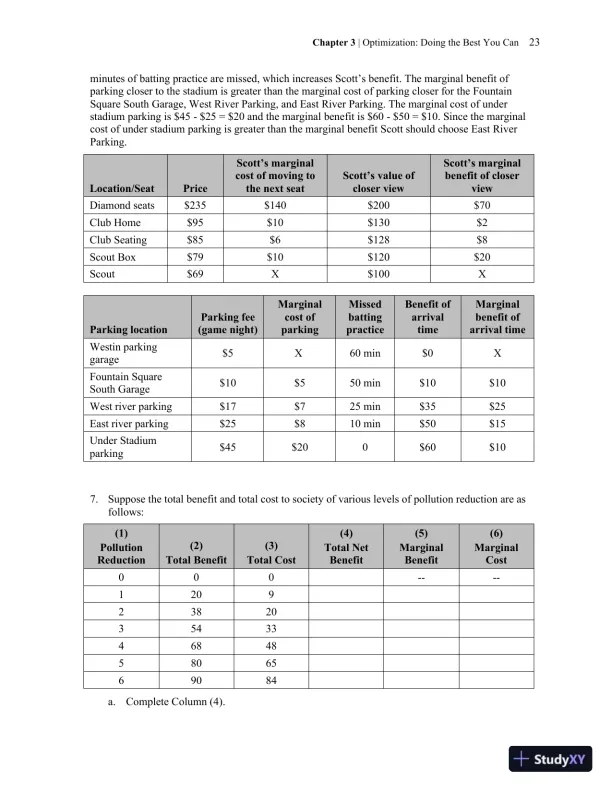

Page 23

Loading page image...

Page 24

Loading page image...

Page 25

Loading page image...

Page 26

Loading page image...

Page 27

Loading page image...

Page 28

Loading page image...

Page 29

Loading page image...

Page 30

Loading page image...

Page 31

Loading page image...